Scientists have discovered a set of detailed genetic markers in African cattle that are associated with valuable traits like heat and drought-tolerance, the capacity to control inflammation and tick infestations, and resistance to livestock diseases like trypanosomiasis.

They hope that this information, coupled with modern breeding tools, can be used to breed indigenous African cattle with more productive European and North American cattle breeds in the future to produce more productive animals whilst retaining key health and resilience traits.

Researchers from the Centre of Tropical Livestock Genetics and Health (CTLGH) based at International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) in Nairobi and Addis Ababa, were part of an international group who sequenced and studied the genomes of 172 indigenous African cattle.

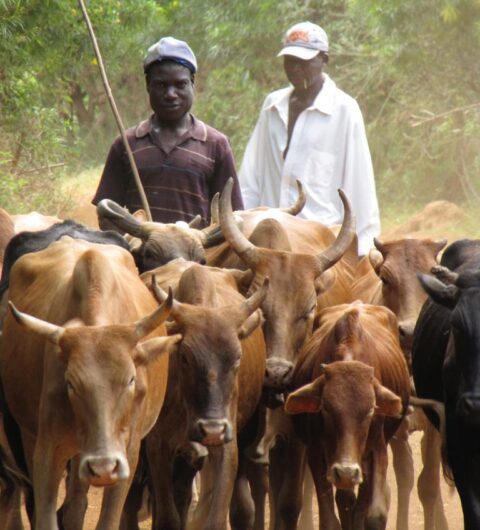

They wanted to learn how, after spending thousands of years confined to a relatively narrow region of Africa, cattle rapidly evolved during the last millennia with traits that allowed them to thrive across the continent.

The findings of this research, which was part funded by CTLGH, was published in the October issue of Nature Genetics. It shows that the arrival of Asian cattle breeds in East Africa 750 to 1050 years ago had a monumental effect on the future genetic development of indigenous African cattle, as they carried genetic traits that would make cattle production possible in a diversity of African environments.

By studying the genomes of indigenous African cattle, the researchers found that African pastoralist herders started to breed the Asian cattle, known as Zebu, with local breeds known as Taurines. The Zebu offered traits that would allow cattle to survive in hot, dry climates typical in the Horn of Africa. By crossing the two, the new animals that emerged carried the key Zebu traits but also retained the capacity of the taurines to endure humid climates where vector-borne diseases like trypanosomiasis are common.

Olivier Hanotte, Programme Leader at CTLGH, Principal Scientist at ILRI and Professor of Genetics at the University of Nottingham was one of the researchers involved in the work. He said:

“We believe these insights can be used to breed a new generation of African cattle that have some of the qualities of European and American livestock—which produce more milk and meat per animal—but with the rich mosaic of traits that make African cattle more resilient and sustainable.”

He added:

“WE’RE FORTUNATE THAT PASTORALISTS ARE SUCH SKILLED BREEDERS. THEY HAVE LEFT A VALUABLE ROADMAP TO SUPPORT EFFORTS TODAY TO BALANCE LIVESTOCK PRODUCTVITY IN AFRICA WITH RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY.”

Today, there are at least 150 indigenous cattle breeds found in Africa, each with unique phenotypic and adaptive characteristics. They play an important role across African economies and societies as a primary source of wealth. They provide nutrition, manure, and draught power and are often used to pay as bride wealth.

As the demand for animal-based protein increases to feed a growing population, the need to improve the productivity and health of tropical livestock is clear. However, researchers cautioned that while increasing yields of milk and meat per animal is crucial, especially to avoid expansion of livestock production into sensitive natural habitats, the focus must remain on raising cattle suited to African environments.

Steve Kemp, Deputy Director of CTLGH and Head of the LiveGene programme at ILRI commented:

“You can see from studying the genomes of indigenous cattle that breeding for environmental adaptation has been the key to successful livestock production in Africa. And that has to be the focus of future efforts to develop more productive but also more sustainable animals.

“If the goal is purely productivity, then you’re doomed to fail.”